Why Israel is calling Palestinian rights groups 'terrorists'

In October, Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz declared six Palestinian civil society organizations “terror groups." In this episode of Unsettled, we look closely at one of those groups, Al-Haq: its founding principles, its role in Palestinian society, and the impact of Israel's terror designation on its ability to continue documenting Israeli human rights abuses.

In October, Israeli Defense Minister Benny Gantz declared six Palestinian civil society organizations “terror groups." These groups work in issue areas like women’s rights, children’s rights, and agricultural labor. The "terror" designation is based on alleged connections to the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, a small political faction. But so far, Israel’s evidence has failed to convince many international leaders. In this episode of Unsettled, we look closely at one of those groups, Al-Haq: its founding principles, its role in Palestinian society, and the impact of Israel's terror designation on its ability to continue documenting Israeli human rights abuses.

This episode was produced by Ilana Levinson and features Jonathan Kuttab and Khaled Elgindy. Archival footage courtesy of Al-Haq.

RESOURCES

Tareq Baconi: Hamas, Explained (Unsettled Podcast, 5/17/21)

‘They targeted us for one reason: We’re succeeding in changing the paradigm’ (Yuval Abraham, +972 Magazine, 10/25/21)

Israeli dossier on rights groups contains little evidence (Joseph Krauss, AP, 11/6/21)

Israel/OPT: Designation of Palestinian civil society groups as terrorists a brazen attack on human rights (Amnesty International, 10/22/21)

Naomi Shihab Nye: Poetry as Refuge

Naomi Shihab Nye is a Palestinian-American writer, educator, and editor. Her published work includes poetry, children’s books and essays, and she has been awarded a Lifetime Achievement award from the National Book Critics Circle. She has also spent decades as an educator, visiting classrooms all around the world.

In this episode, producer Emily Bell speaks with Naomi Shihab Nye about finding inspiration in her father's notebooks, processing grief, and writing about Palestine. Naomi shares a selection of old and new works, including two from her book "Transfer."

““Grief is something that, alas, as human beings we’re just going to keep experiencing over and over and over again in all of its many manifestations. And I think poetry can help us know that we’re not alone in experiencing it, that it’s a place to place our pain, and to place our unresolved questions, our mysteries.””

Naomi Shihab Nye is a Palestinian-American writer, educator, and editor. Her published work includes poetry, children’s books and essays, and she has been awarded a Lifetime Achievement award from the National Book Critics Circle. She has also spent decades as an educator, visiting classrooms all around the world.

In this episode, producer Emily Bell speaks with Naomi Shihab Nye about finding inspiration in her father's notebooks, processing grief, and writing about Palestine. Naomi shares a selection of old and new works, including two from her book "Transfer."

CREDITS

Unsettled is produced by Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, Max Freedman, and Ilana Levinson. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

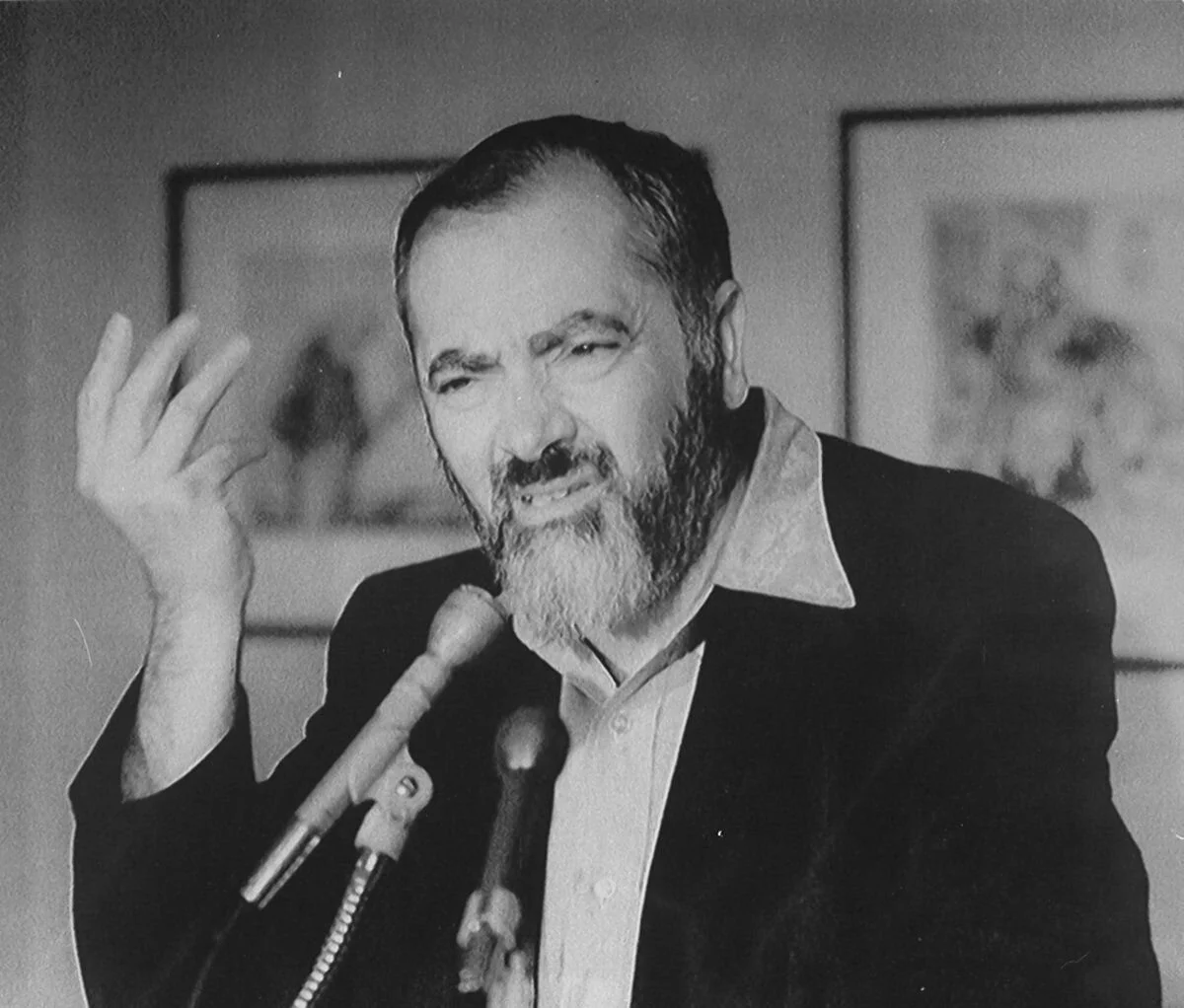

(Episode Image: Dominican University/Flickr)

(Headshot: Michael Nye)

BIO

Palestinian-American writer, editor and educator Naomi Shihab Nye grew up in Ferguson, Missouri, Jerusalem, and San Antonio, Texas, where she continues to live.

She is the Young People’s Poet Laureate of the United States (Poetry Foundation). Her late father Aziz Shihab was a journalist and author of Does the Land Remember Me? A Memoir of Palestine. She has been a visiting writer in hundreds of schools and communities all over the world for more than 40 years and has written or edited 35 books including collections of poetry, novels for teens, picture books, essays, very short fictional stories, anthologies of poetry. Her books Sitti’s Secrets, Habibi, This Same Sky, & The Tree is Older than You Are: Poems & Paintings from Mexico have been in print more than 20 years. Her volume 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems of the Middle East, was a finalist for the National Book Award. Recent books include Everything Comes Next, Cast Away, The Tiny Journalist, and Voices in the Air. She is on faculty at Texas State University and won recent Lifetime Achievement Awards from the National Book Critics Circle and the Texas Institute of Letters. The Turtle of Oman (Greenwillow) a novel for children set in Muscat, will soon be followed by its sequel The Turtle of Michigan.

RESOURCES

“This Court Decision in the Gavin Grimm Case Will Bring Tears to Your Eyes” (American Civil Liberties Union, 4/10/17)

“A memorial to a great Arab American Journalist, Aziz Shihab” (Ray Hanania, The Arab Daily News, 10/28/07)

“Texas journalist Aziz Shihab on 'Does the Land Remember Me?: A Memoir of Palestine'" (Michael King, The Austin Chronicle, 7/20/07)

Marwa Fatafta: Digital Rights

In the spring, the prominent twin activists Muna and Mohammed al-Kurd were regularly speaking out about an Israeli settler takeover of their home in Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem. But just after Muhammad and Muna started to get international attention, they were detained and interrogated by Israeli authorities. The al-Kurd twins are not alone. Palestinians say they’ve been subject to censorship from social media companies and by the Israeli authorities for decades. On this episode of Unsettled, Marwa Fatafta, the Middle East and North Africa Policy Manager at Access Now, talks about censorship of Palestinian voices.

In the spring, the prominent twin activists Muna and Mohammed al-Kurd were regularly speaking out about an Israeli settler takeover of their home in Sheikh Jarrah in Jerusalem. But just after Muhammad and Muna started to get international attention, they were detained and interrogated by Israeli authorities. The al-Kurd twins are not alone. Palestinians say they’ve been subject to censorship from social media companies and by the Israeli authorities for decades. On this episode of Unsettled, Marwa Fatafta, the Middle East and North Africa Policy Manager at Access Now, talks about censorship of Palestinian voices.

CREDITS

Unsettled is produced by Ilana Levinson, Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, and Max Freedman. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Marwa Fatafta leads Access Now’s work on digital rights in the Middle East and North Africa region as the MENA Policy Manager. She has written extensively on technology, human rights, and internet freedoms in Palestine and the wider MENA region. Marwa is also a Policy Analyst at Al-Shabaka: The Palestinian Policy Network where she co-led the organization's policy work on questions of Palestinian political leadership, governance, and accountability. Previously, Marwa was the MENA Regional Advisor for Transparency International Secretariat in Berlin and served as the Communications Manager at the British Consulate-General in Jerusalem. Marwa was a Fulbright scholar to the US, and holds an MA in International Relations from Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, Syracuse University. She holds a second MA in Development and Governance from University of Duisburg-Essen.

RESOURCES

Access Now's statement on Facebook and Twitter systematically silencing protests (5/7/2021)

Access Now's 'Facebook Stop Silencing Palestine' campaign

"Elections or not, the PA is intensifying its authoritarian rule online" (Marwa Fatafta, +972 Magazine, 4/29/21)

“Facebook's Secret Rules About the Word 'Zionist' Impede Criticism of Israel" (Sam Biddle, The Intercept, 5/14/21)

Introducing Groundwork

Groundwork is a new podcast about Palestinians and Jews refusing to accept the status quo and working together for change. When war broke out between Israel and Gaza this past May, some of the worst inter-ethnic fighting in Israel’s history erupted between its own citizens. The violence showed that even in mixed cities, where people often talk of coexistence, there are deep political, ethnic, and economic divides.

Groundwork is a new podcast about Palestinians and Jews refusing to accept the status quo and working together for change. When war broke out between Israel and Gaza this past May, some of the worst inter-ethnic fighting in Israel’s history erupted between its own citizens. The violence showed that even in mixed cities, where people often talk of coexistence, there are deep political, ethnic, and economic divides.

Lod was the epicenter of this recent violence: there were shootings in the streets, neighbors attacking one another, lynching. In this episode, Groundwork’s hosts Dina Kraft and Sally Abed speak with Lod activists Rula Daood and Dror Rubin about the complicated history of Lod, what they think led to the violence in May, and what’s next.

CREDITS

Sally Abed is a staff member and an elected member of the national leadership at Standing Together. In recent years, Sally has become a prominent Palestinian voice in Israel that is putting forward the holistic view that identifies the interrelation between the ongoing occupation of Palestinian territories, growing social and economic disparities within Israeli society, the threat of climate change, and attacks by the government on democratic freedoms and Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel.

Dina Kraft is a veteran foreign correspondent based in Tel Aviv where she’s The Christian Science Monitor correspondent. She began her overseas career in the Jerusalem bureau of The Associated Press. She was later posted to AP’s Johannesburg bureau where she covered southern Africa. She’s also reported from Senegal, Kenya, Pakistan, Jordan, Tunisia, Russia, and Ukraine. Dina has taught journalism at Northeastern University, Harvard University, and Boston University. She was a 2012 Nieman Fellow at Harvard University, and a 2015 Ochberg Fellow at the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University.

Dina hosted “The Branch” podcast, about ties between Jews and Palestinians and her work has also been published in The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and Haaretz among other news outlets.

Yoshi Fields is the co-founder and producer of Groundwork and has worked in the podcast industry for about 5 years. In 2018, he moved to Israel-Palestine and has worked on several podcasts in the region, focusing on both political and human interest stories, including as a producer at Israel Story, The Branch, and Unsettled.

Through his work, Yoshi aims to empower the voices of others, and facilitate the expression of their stories. He has previously hiked the Himalayas while carrying out a research study on the intersection of love and Buddhism, and worked in a hospice for a year writing about the experience of mortality for health workers.

Groundwork is powered by the Alliance for Middle East Peace and the New Israel Fund.

Jonathan Brenneman and Aidan Orly: Christian Zionism

As international attention turned to Israel-Palestine this May, Jonathan Brenneman and Aidan Orly co-authored an op-ed for Truthout titled “Progressives Can’t Ignore Role of Christian Zionism in Colonization of Palestine.” In this episode, producer Emily Bell interviews Brenneman and Orly about the origins of Christian Zionism; the relationship between Christian Zionism, Jewish Zionism, and U.S. foreign policy; and what it means to challenge Christian Zionism.

“So long as we’re not talking about Christian Zionism, we are complicit in allowing them to continue to be influential and be powerful, and that is a huge threat to Palestinians, [a] huge threat to Muslims, and also a huge threat to Jews.”

As international attention turned to Israel-Palestine this May, Jonathan Brenneman and Aidan Orly co-authored an op-ed for Truthout titled “Progressives Can’t Ignore Role of Christian Zionism in Colonization of Palestine.” In this episode, producer Emily Bell interviews Brenneman and Orly about the origins of Christian Zionism; the relationship between Christian Zionism, Jewish Zionism, and U.S. foreign policy; and what it means to challenge Christian Zionism.

credits

Unsettled is produced by Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, Max Freedman, and Ilana Levinson. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Jonathan Brenneman is a Palestinian-American Christian. He has undergraduate degrees in History and Philosophy from Huntington University, and in 2016 completed a Masters at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies. Before going to Notre Dame, Jonathan was part of Christian Peacemaker Teams Palestine project in Hebron/Al-Khalil, where he worked in solidarity with Palestinian communities to challenge unjust Israeli policies and the structures that uphold them. Today, he continues his advocacy in the United States primarily through challenging Christian Zionist theology.

Aidan Orly is an Israeli-American Ashkenazi Jew who is active in donor and social justice organizing, especially around issues related to Jewish communities, the Christian Right, and Palestine.

RESOURCEs

“Progressives Can’t Ignore Role of Christian Zionism in Colonization of Palestine” (Jonathan Brenneman & Aidan Orly, Truthout, 5/20/21)

“Will this Palestinian matriarch get to keep her Jerusalem home?” (Unsettled, produced in collaboration with +972 Magazine, 4/12/21)

“Inside the Most Insanely Pro-Israel Meeting You Could Ever Attend” (David Weigel, Slate, 7/22/14)

“An unholy alliance” (Natasha Roth-Rowland, +972 Magazine, 11/5/20)

“The Terrifying Alliance Between End Times Christian Zionists and Donald Trump” (Sarah Lazare, In These Times, 10/5/20)

“AIPAC Isn’t the Whole Story” (Jonah S. Boyarin, Jewish Currents, 3/4/19)

Kathleen Peratis: Visiting Gaza

Two million people live in the Gaza Strip, and they’ve endured over a decade of air raids, and an economic blockade that deprives them of basic necessities, like power and clean water. But in the Jewish community, conversations about Gaza tend to focus only on Hamas terrorism and claims of widespread antisemitism. Kathleen Peratis has been to Gaza five times in the last decade, and what she saw there tells a very different story. In this episode, Kathleen talks about what she learned from her experiences in Gaza and the people she met while she was there.

The Gaza strip has been under Israeli siege for 14 years, with cycles of violence happening over and over again. In the latest round of fighting, at least 254 Palestinians and 13 Israelis died. 2 million people live in the Gaza strip, and they’ve endured over a decade of air raids, and an economic blockade that deprives them of basic necessities, like power and clean water. But in the Jewish community, conversations about Gaza tend to focus only on Hamas terrorism and claims of widespread antisemitism. Kathleen Peratis has been to Gaza five times in the last decade, and what she saw there tells a very different story. In this episode of Unsettled, Kathleen talks about what she learned from her experiences in Gaza and the people she met while she was there.

Unsettled is produced by Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, Max Freedman, and Ilana Levinson. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Kathleen Peratis is a Partner at Outten and Golden, an employment justice law firm in Manhattan. She's also the Co-Chair of the Middle East and North Africa Division for Human Rights Watch, and the former director of the Women’s Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union, succeeding Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Kathleen's published works on her time in Gaza:

Unsettled's 4-part series on Gaza:

Update from the South Hebron Hills

The recent escalation of violence in Israel-Palestine seemed to be happening everywhere, all at once. But one place that’s been getting less public attention is a rural part of the West Bank called the South Hebron Hills. Last weekend, Jewish settlers set fire to Palestinian fields and tried to destroy a cave in the village of Sarura.

We have dedicated two past episodes of Unsettled to the story of this cave: how it was first reclaimed four years ago by Palestinian and Jewish activists; and how it has remained in local Palestinian hands ever since, thanks to a group called Youth of Sumud. Today, we’re sharing those two episodes as one.

The recent escalation of violence in Israel-Palestine seemed to be happening everywhere, all at once. But one place that’s been getting less public attention is a rural part of the West Bank called the South Hebron Hills. Last weekend, Jewish settlers set fire to Palestinian fields and tried to destroy a cave in the village of Sarura.

We have dedicated two past episodes of Unsettled to the story of this cave: how it was first reclaimed four years ago by Palestinian and Jewish activists; and how it has remained in local Palestinian hands ever since, thanks to a group called Youth of Sumud. Today, we’re sharing those two episodes as one.

Unsettled is produced by Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, Max Freedman, and Ilana Levinson. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

“Palestinian children travel dangerous route to school in At-Tuwani” (DCI Palestine, 9/10/13)

Amira Hass and Hagar Sheizaf, “The Village Where Palestinians Are Completely Powerless” (Haaretz, 1/5/21)

Spotify playlist: Unsettled essentials, May 2021

transcript

MAX FREEDMAN: Hey, this is Max, one of the producers of Unsettled.

One of the unique things about this moment in Israel-Palestine is that violence has been escalating everywhere, all at once. We’ve talked on the show about Jerusalem, Gaza, Haifa, and Lydd, just to name a few.

But one place that’s been getting less public attention so far is the South Hebron Hills, a rural part of the West Bank where I spent time in late 2019 and early 2020. Settler violence, which is a constant in the South Hebron Hills, has been ramping up too.

Last weekend, Israeli soldiers and police looked on and did nothing as masked settlers set fire to Palestinian fields. A local activist named Sami Huraini put this video on Facebook.

SAMI HURAINI: English now. So now we are live from the village, near the village of Tuwani in the South Hebron Hills. A lot of settlers are attacking in this moment the Palestinians. Under the protection of the Israeli occupation soldiers. A while ago, the settler just set up a fire in al-Haruba that’s very near from here 5 minutes. With as we can see we are hearing the shooting of the tear gas and sound bombs by the Israeli settlers against the Palestinians. At the moment the settlers are… looks like going back. Or no, they are still here. The soldiers are shooting rubber bullets. The soldiers are shooting the rubber bullets against the Palestinians.

MAX: While Sami and his friends were busy documenting the settlers and dodging rubber bullets, another group of settlers saw an opportunity. They went to the Palestinian activists’ cave in a nearby village called Sarura. Here’s another video posted to the Facebook page of Sami’s group, Youth of Sumud.

ACTIVIST: I’m here in Sarura. Settlers have put fire to the cave inside. I don’t know if you can see. And also to the field outside. We have policemen standing on the hill and they’re not doing anything. They saw the settlers come, they saw them light the fire, they’re continuing to stand there. We’ve called the police a dozen times and they’re not responding. And the land is continuing to burn. This is in Sarura in the South Hebron Hills.

MAX: According to Sami Huraini, the settlers burned furniture and a generator inside the cave, destroyed the wall of their kitchen, their water tanks, and their bathroom.

This cave is not just a cave. This cave is so significant that we have dedicated not one, but two episodes to its story: how the cave was first reclaimed by Palestinian and Jewish activists four years ago, and how it has remained in local Palestinian hands ever since. Today, we’re sharing those two episodes as one.

Up first is our very first episode, from way back in August 2017.

PART 1: SUMUD FREEDOM CAMP (2017)

TOM CORCORAN: We are live here at Sumud Freedom Camp in the Palestinian village of Sarura, where the Israeli military has moved in and started to take down our tents and push back on nonviolent protestors…

ILANA LEVINSON: Today’s episode takes place in the South Hebron Hills, where activists including Tom Corcoran, whose voice you just heard, gathered in May. The South Hebron Hills is an arid area of the West Bank that is part of Area C — under full control of the Israeli military.

With the systematic expansion of Israeli settlements and pressure from the military, the Palestinians who live in the area are at constant threat of home demolitions and displacement. And in some villages, no structures or people remain.

Fadal Amer used to call the cave-dwelling village of Sarura home, but he was forced out in 1997 by violence from nearby Israeli settlers who burned his crops and poisoned his wells. Two years later, the IDF declared Sarura part of Firing Zone 918, evicting the remaining residents. Though Fadal was forced to leave 20 years ago, the key to his cave still hangs off of his belt.

This May, Fadal Amer attempted to return home, with the support of a historic coalition of Israelis, Palestinians, and diaspora Jews. Marking the 50th year of the Israeli occupation of the West Bank, the activists gathered together to establish Sumud Freedom Camp, with the hope of reclaiming Sarura not just for Fadal, but for the whole community to someday return.

Sumud, built where Sarura once stood, translates in Arabic to steadfastness. Sumud became not just the name of the camp but also the coalition’s rallying cry, as activists took to social media with the hashtag #WeAreSumud. But despite the historic coalition, and social media efforts, the story of Sumud has largely been absent from mainstream news.

As fear and uncertainty overwhelm the region, it's hard to imagine such an unprecedented coalition of Israelis, Palestinians and diaspora Jews coming together. But today we’ll dive into just such a story. But today we'll hear from three American Jewish activists that were there, with their Palestinian and Israeli partners, building Sumud together, from the ground up.

I'm Ilana Levinson, and welcome to Unsettled.

MUSIC: Unsettled theme

ILANA: Unsettled is a new podcast about Israel-Palestine and the Jewish diaspora. We’re here to provide a space for the difficult conversations and diverse viewpoints that you might not hear in institutional American Jewish spaces.

I'm one of the producers of Unsettled and your host for today's episode.

While many different people were involved in building Sumud Freedom Camp, in this episode we’ll hear the perspective of three American Jewish activists who helped establish the camp, including Tom, who you heard from at the very beginning. Just a few weeks after returning to the US, they sat down in my living room in NYC to tell their story.

JEREMY SWACK: My name is Jeremy Swack, and I’m most recently involved in Open Hillel, though I’ve been involved in various other organizations including IfNotNow and J-Street U.

TOM CORCORAN: My name is Tom Corcoran and I’m a member of IfNotNow based in New York.

NAOMI DANN: I’m Naomi Dann and I work with Jewish Voice for Peace.

ILANA: Jeremy, Tom, and Naomi were there with the Center for Jewish Non-Violence, one of the organizations that formed the coalition. And after months of planning, they along with more than 300 activists prepared to march to Sarura on Friday, May 19. But secrecy was needed.

JEREMY: because it was uncertain that we would even be able to access the land.

ILANA: In fact, most of the group was kept in the dark about some key details until the very last minute--including the name and location of the village itself.

NAOMI: We didn’t know what it was, no one knew what it was, that was like the most closely kept secret cuz we knew that the army could easily put up a checkpoint and prevent us from getting to the land we were going to.

JEREMY: That’s why part of our group went down the night before and slept in a village nearby to ensure that at least some of us would be able to get there.

ILANA: Tom was one of those who camped close to the meetup site.

TOM: There were about 60 of us, we stayed on a roof, it was pretty uncomfortable actually.

ILANA: The next morning though, the army didn't stop anyone, and the activists from the 6 organizations: the Center for Jewish Nonviolence, Combatants for Peace, Holy Land Trust, Youth Against Settlements, All That’s Left: Anti-Occupation Collective and Popular Resistance Committee for the South Hebron Hills came together to march to Sarura. Fadal Amer led the group, as people chanted and waved flags. Issa Amro, founder of Youth Against Settlements, was among those who led chants.

ISSA AMRO: 1-2-3 (1-2-3) / Palestine will be free (Palestine will be free)

ILANA: But while there was lots of excitement, there was also discomfort.

NAOMI: I know that most American Jews have never been in a rally with Palestinian flags, and often that’s really triggering or scary or super uncomfortable for people, and all of a sudden, it was this really politically diverse group of Jews, working like very much following the lead of Palestinians who had designed this camp, and working alongside Israeli activists and Palestinian activists, and people had a Palestinian flag in their hands for the very first time, and I looked a couple of people, and they looked at their hand, and looked at the flag, and it was okay! And it was great. And it was like, this actually feels right in this moment.

TOM: One of the most powerful things was waving Palestinian flags, joining together as a coalition and coming into the land, a land that people had not been able to be in for decades.

ILANA: When the group arrived at Sarura, there was barely a trace of the cave dwelling village that had once stood there - a few broken down walls in an otherwise deserted landscape.

TOM: After 20 years of not being used, there was a lot of work to do.

ILANA: Knowing that settlers or the army could arrive at any time, the activists got to work. Some followed Fadal Amer to his cave

NAOMI: He was wearing a key that hung off of his belt: a big rusty key that fit the lock on the gate that entered the cave that he had been born in and that we were reclaiming with him

ILANA: Like Fadel Amer, many Palestinians still carry the keys to their old homes. The key is a symbol of the “right of return,” a movement that began in 1948, when Palestinians were displaced during the establishment of Israel.

NAOMI: A lot of people left with their keys in their pockets, and didn’t know that they would never be able to go back, and so those keys are really powerful, and it was amazing to see--he was literally wearing that key, and we could be there for the moment where he could use that key again.

TOM: Seeing Fadel returning to his cave, finally opening that door for the first time, that was something that was just undeniable, it felt right to be there and to be doing this work and supporting that work.

ILANA: In order to build the camp, as well as restore the caves, groups of activists hurried to rebuild stone walls -- and cleared out bugs from inside caves. Others began setting up a large tent:

TOM: The simple act of doing that physical labor together: digging out rocks, moving them around, setting up a wall, setting up a tent--being able to do that, it was a huge equalizer, and it was really humbling.

ILANA: As work progressed, Fadel Amer spent time with the activists. While he spoke both Arabic and Hebrew, some of the Americans only knew English.

NAOMI: he was the most warm and welcoming person and you didn’t need a shared language to know that. Like, full of smiles, and he was greeting everyone, constantly checking in on everyone.

JEREMY: I think he really spoke to the Palestinian culture of not just hospitality but immense generosity. He was really hosting us in a lot of ways, even though we were hoping to build Sumud Camp, this was his home, and he had invited us to his land and to his home to do this work.

ILANA: Still, even this homecoming was shadowed by the threat of confrontation.

NAOMI: We started establishing things that felt more permanent, and we started looking over our shoulders, like “Okay, when’s the army going to come?” We know that this is a firing zone, they’ve forbidden Palestinians to be here, and they could come at any time and kick us out.

ILANA: But as the sun set, those in the camp who observed shabbat gathered together. Amid more traditional shabbat music, Souli Khatib from Combatants for Peace played the flute.

JEREMY: I think there was a certain point, after we had been there about a day, I felt very comfortable in the camp, and believed that the camp would continue to thrive, even though in the back of my head I intellectually knew that the camp was probably going to be destroyed, which it ended up being. And that was just a really big wake up call. I think for me and for many of us, was a tiny window into what living under occupation is, is you’re not sure when the army is going to come and destroy anything.

ILANA: The next day, as some continued to observe the sabbath and rest, others continued to work. While cement was mixed and poured on the floor of Fadal Amer’s cave, music played, people danced and there was even a makeshift game of limbo.

Saturday night the group gathered in the large tent for Havdalah, a Jewish ceremony marking the close of Shabbat. Among the songs they sang was an adaptation of the anti-Apartheid song, “Courage.”

ACTIVISTS: Sarura / My friend / You do not walk alone / We will / Walk with you / And sing your spirit home

NAOMI: it was late midnight on Saturday, we had bonfires going, we had music playing, people were still cooking food, and all of a sudden, there were a series of lights that came over the hill, and within like 10 seconds we all realized that the army was coming into the camp.

TOM: They went straight for our generator, they went straight for some of the tents and structures we had set up.

ILANA: Many of the activists began recording and livestreaming on Facebook, creating hundreds of witnesses around the world. Despite having no demolition order, the army quickly destroyed most of the camp.

NAOMI: We went back and forth between being totally totally powerless, because there was nothing that we could do, because we were up against such a force that had so much power, and also so powerful, to be holding hands with people who I trusted, who I’d built community with.

ILANA: When all that remained was the large tent, the activists responded quickly. Jeremy and others who made it inside, linked arms in the darkness. The army began tearing down the tent and tried to break the group apart:

ACTIVISTS: You’re hurting him! You’re hurting him! You’re hurting him! You’re hurting him! You’re hurting him! Please! Please! We are nonviolent! We are sitting in our campsite in peace!

ILANA: Gathered close, and low to the ground as the soldiers loomed over them, they turned to song.

ACTIVISTS: We will build this world with love / Dai dai dai dai dai dai dai dai / We will build this world with love / Dai dai dai dai dai dai dai dai

ILANA: Outside the tent, Tom and the rest of the activists were steps away from another group of soldiers. As they chanted and sang, Tom livestreamed the raid:

TOM: We are here because we believe in freedom and dignity for all peoples. We believe in the right of Palestinians to their lands. We are here protesting against fifty years of occupation. And we are here as part of a nonviolent resistance.

TOM: I saw what we were doing, the risk we were taking, and I knew the risk our Palestinian partners, that Fadal, that the people who were returning to Sarura were taking just by being there, and the risks that they face every day, and for me, that was something where we had to film it, we had to report back on it, because there was something so viscerally brutal.

ILANA: With the tent almost fully collapsed, the activists stood in a tight formation and grasped at the tarp in fistfulls. At the direction of a Palestinian leader, they lowered the tarp and sat on top, relinking arms. From Jeremy's recording you can hear as the army continued to cut and tear the tent from underneath them.

ACTIVISTS: When the world is sick / Can no one be well / But I dreamt we were all beautiful and strong

ILANA: After about an hour - almost no structures remained. With part of the tarp confiscated - the army began loading back into their trucks. As the army left, the activists chanted a promise.

ACTIVISTS: We will rebuild (together)! We will rebuild (together)! We will rebuild (together)! We will rebuild (together)!

ILANA: The group gathered amid the strewn mattresses and belongings. The medics attended to those who had been punched, kicked and choked. Others sent messages and updates to the world. A fire and sleeping space was quickly assembled.

While some went to rest, Tom joined the nightwatch in case settlers or soldiers returned again. Tom recounted sitting around the fire with Palestinians, including three men from the town of Umm-El Khair who had partnered with their group - the Center for Jewish Nonviolence- earlier in the week.

TOM: We were tired, we were cold, we were out there, and then they were just there making tea for us, or didn’t have sugar for tea so instead gave us some mango juice, and it was just like this thing where, okay there’s work to be done and we need to set up and this was a hard moment, but we can still spend time with each other and take care of each other and sit around a fire in the middle of the night. And so that was something where, though I was exhausted, being able to have that experience immediately after was really moving and really healing.

ILANA: When the activists woke up on Sunday morning, the army had not returned. Before starting to rebuild they gathered in a circle.

ACTIVISTS: Light is returning / Even though this is the darkest hour / No one can hold back / Back the dawn

JEREMY: It was definitely a moment for me that solidified what Sumud means: Steadfastness. In that, immediately as Tom said, some people began to rebuild, and when we woke up in the morning, we were rebuilding that camp.

ILANA: Using the tarp that the army had not confiscated, they rebuilt the tent in front of Fadel’s cave. Though there was more work to be done, the Center for Jewish Nonviolence delegation had to leave later that afternoon.

TOM: there was this really deep feeling that we were just leaving the people that we had worked with and built this camp with, and even though that was always part of the plan, that as the Center for Jewish Nonviolence we were going to be there for that specific amount of time and then leave… I don’t know, I felt a lot of guilt. And I think that it’s our responsibility to bring this message back. But it also felt hard to not still be there and keep the work going.

ILANA: But before they left, Fadel addressed the group outside his cave.

JEREMY: He spoke to us through a translator, and he actually apologized for the events that had happened in the Israeli raid the previous night, which… is just unbelievable, that he apologized to us for that. That was...really something. I don’t know what to say about it.

ILANA: Two weeks after returning from Palestine, when we recorded this interview, Naomi, Jeremy and Tom were still processing their time at Sumud. We asked them how the story of Sumud was being received by the American Jewish public.

NAOMI: Well… I don’t know how many people in the American Jewish community know about it still. And I think the point of the trip was to be American Jews there experiencing occupation and taking part in this direct action that would get some press that would tell a story to people back home to change their minds? And I think that was the right approach and strategy for that plan, but there hasn’t been enough attention on it.

ILANA: Naomi gave a couple reasons for this, including Donald Trump’s visit to Israel which happened at the same time, but also:

NAOMI: It didn’t make as much news because I think the army played us really smart. They didn’t destroy the camp totally, they let us rebuild, they didn’t arrest people so there wasn’t something to rally around, and the media wasn’t there that first day because there wasn’t violence and the media follows violence, and so it wasn’t as big of a story as we had hoped it would be.

ILANA: And some who have heard about Sumud have criticized the action, arguing that no one is allowed to live in Sarura, and the army’s destruction of the camp was justified. They argue that the activists should not have been there in the first place. But Naomi sees it differently.

NAOMI: I mean, that is the whole history of civil disobedience, is about breaking laws that we believe are unjust, and so people who make that argument are missing the point. The reason we were there to say these laws are unjust and the way the system is set up is unjust. And so that’s why we’re going to go directly against it. And some of the most powerful civil disobedience actions are when you literally break the law you’re going to change in order to make a statement about how it needs to change.

ILANA: The people of Sarura and others from evicted villages in Firing Zone 918 have been fighting in the Israeli courts to have their homes back, but not only have they not been allowed to return, they also haven't been given any compensation for the land they lost.

TOM: It’s not possible for a Palestinian to get permission to build on that land. Even while at the same time there’s a settlement that we could see, the entire time, just right there.

ILANA: But, they still felt that their presence - the American and International presence at the camp - had enabled the the story of Sumud to reach more people than it otherwise would have.

TOM: People i know in my life, or people in the lives of people who were on the trip who paid attention because they were there, or because American Jews were there. Whereas if it were just something happening to palestinians, or some Israelis in support, it wouldn’t have gotten as much attention. That’s absolutely true.

ILANA: Furthermore, the story of Sumud’s construction wasn't just an attempt to make news or about the resulting nighttime raid, which is what the news so often focuses on.

TOM: And then the other part is that it wasn’t just for show. It was fadal, his family, people actually coming back to Sarura and being able to enter their homes for the first time in at least 20 years. So knowing that this possible and that that is still happening, that’s really powerful, and that’s also a story that we need to be sharing and we need to be continuing to get out there.

ILANA: But perhaps the greatest obstacle for sharing this story is how hard it can be to talk about the occupation

NAOMI: I talked to a lot of people who feel really disempowered to talk about what’s happening, and they say “Oh, like Israel-Palestine conflict…” I’ve been told “It’s too complicated, I have never really been there, I don’t feel like I’m an authority to be able to speak about it.” I work really hard to help people dispel that fear. Yes it’s complicated, yes there are multiple narratives, yes, the history is really complex, and also it’s very very clear that something really wrong is going on what’s happening right now is a pretty simple wrong.

JEREMY: Since I’ve been back, when people have asked me “What was it like, how was your experience”-- the only thing I’ve really been able to muster is, saying at first, “The occupation is really really really really bad.” And I think that speaks to what Naomi was saying, that this is simply a wrong. There is complexity and narratives and history and whatnot but the occupation itself is wrong, must be ended, and we as diaspora Jews hold immense power in ending it.

TOM: It’s not just a distant system, it something that people enforce, and it’s something that many enforce with cruelty. UM and that’s something that I think people need to know, that it’s not just about, oh, there are all of these competing narratives. It’s also a lived reality, where people’s movement and rights and lives are restricted. I think that’s just something that being there, was so undeniable. And that’s something I’m committed to continuing to make that known to people who are in my life and people I have these conversations with. It’s...yeah. It’s not a myth. It’s very very real.

PART 2: YOUTH OF SUMUD (2021)

MAX: So ever since we released that episode in 2017, I’ve been wondering... what happened to Sarura after the internationals left? And about a year ago, I got to see for myself. In fact, I spent New Year’s Eve in the very same cave.

That was only possible because of a group called Youth of Sumud, which was created in the wake of that 2017 action. How they have maintained this cave for almost four years, and the risks they have taken to do so -- that’s the subject of this episode.

My name is Max Freedman, and this is Unsettled.

MUSIC: Unsettled theme

MAX: Samiha Huraini is one of the founders of Youth of Sumud. When we spoke, on December 31, 2019, she was 20 years old, studying English literature at university.

The part of the West Bank where Samiha lives, and where Youth of Sumud does most of their work, is called the South Hebron Hills. It’s also known as Masafer Yatta, in reference to the nearby city of Yatta. Over the last couple of decades, a lot of people whose families have roots in this area have had to move to Yatta -- for jobs and education, but also often because Israeli authorities have confiscated or destroyed their homes, and prevented them from building any infrastructure. Many experts say that this is part of a broader strategy of packing Palestinians into cities, so as to open up more and more of the land of the West Bank for Jewish settlement.

As I sat with Samiha on a couple of big rocks near her home village of Tuwani, all around us, there were activists planting olive trees. In the road just below us was a unit of Israeli border police, watching. And behind them, perched on the top of a hill, a walled settlement.

Here’s my conversation with Samiha Huraini.

MAX: So my friend Emily was here a couple of years ago and she was at the sumud freedom camp with CJNV. Was that before or after you started youth of Sumud?

SAMIHA HURAINI: No. Uh, you know, at the beginning of the, uh, of the camp of the idea of this village, there there was a lot of international people, uh, Jewish, uh, fighting for, uh, against occupation, non violent, uh, that were supporting this, uh, this idea just, uh, step by step that people to start to leave and leave so the people start to be few and then everyone leaved. So the village became alone again. So that here Youth of Sumud born that, uh, we have to complete what the others was doing and to lead this idea until the end.

MAX: Since they built the camp in Sarura with the caves. So you. Since and the internationals left. So youth of Sumud you had to stay there every night in order to keep it from being torn down. Is that what did what did you have to do in order to keep it from being destroyed?

SAMIHA: We have to stay there 24 hours. They have to feel that there is a Palestinian people there and we have to back the family again. We have to encourage the family to back again because it just the one solution that we can protect the village. You have done it to encourage and to make the people interesting to back again. You know, it's really difficult to back up like people for their own houses, or own cave. After twenty years, you cannot imagine what violent that they saw. That they feel. That how much was hard for them to leave their home. Just they leave it because I'm, I'm sure that they saw very big of violent they was scared about their children life, their own life, their wife life. So they just escape from that because that the the more the violence that they saw when they live in that village every night and every morning. And. And as I told you, there is no life service no electricity no water nothing. Also encourage you to stay. So there was there was stopped anything that you are going to do to make you strong and stay there. They cut the water. They cut the electricity. There is nothing, nothing to make you stay there. So they make you weak and weak and weak. Just go. And scare you scare your children. For so that people for sure was scared for their children and for their life. So they just go. So now it's really difficult to back them again. So after one year of cleaning, restorate and, uh. Bring attention and make it bigger and cleaning, everything's preparing. We decide they came like three or four times in the weekend. And slept and preparing their stuff. And in their caves. [104.1s]

VOICE: One minute.

MAX: Someone has approached Samiha with news. They speak in Arabic for a while. Remember, it’s December 31st.

SAMIHA: So I'm preparing for the evening things, evening party, and he was asking me to go for the camp now.

MAX: Okay, you need to go now?

SAMIHA: All of us.

MAX: Oh okay. We all need to go now.

SAMIHA: Yeah. Because they make this area closed military zone so we cannot do our activity here. So we have to move.

MAX: How did you find. How do you find out when they decide it's a closed military zone?

SAMIHA: It just stops. Well, I don't know. You know, this is crazy that something you are planning for it like months. And they just come and tell you you cannot do that closed military if you will be there. You'll be arrested or you'll be. It's something.

MAX: So so the place where we were going to do the event, the party tonight. We can't do it there anymore? Is that what he said?

SAMIHA: Yeah. And we have to go to do it in the camp. In the cave.

MAX: We have to go and do it in Sarura.

SAMIHA: In the cave yeah.

MAX: Instead. Okay.

SAMIHA: Yeah.

MAX: So that's where we're gonna. We're gonna go to Sarura now.

SAMIHA: Yeah. Was planning to light that big tree in the Sumud Freedom Garden that also it's one of the ideas of Youth of Sumud. Just it will not go. It will not work. All of us will be arrested. And we don't want that for anyone. And they will confiscate everything you will have it here, so. We can go there to do it. They will not stop the idea just they stop us to be here in the place. So, just we will celebrate it together in Sarura.

MAX: So so the family that the family that used to lived in Sarura a long time ago, they have not moved back.

SAMIHA: No, because it was destroyed before we start to work on it. It's really was destroying. There was no life, nothing. It was really just, uh, caves full of stone and rubbish that the settlers was putting inside to make it's dirty, to destroy it, to don't make it's able to be life again. The old people that they used to live, the grandfather of mom and dad's caves that was they was died. So now their sons and their daughters that living in Yatta that we are encouraging them to come back. So now weekly, they came three, four time and, uh, they came start to bring their stuff. They started prepping their caves with their stuff. So it's for us a big succeed.

MAX: So they're so there are still people from there, still people from youth of Sumud who stay there 24 hours a day, all these years later.

SAMIHA: Yeah. Yeah for sure. So some of us is here. Some of them was in the camp. So we cannot leave it like all of us come and focus on this action and leave the caves. No. You have to always be, uh, some of us have to be there. To be, uh, not one. For sure.

MAX: And at the beginning, all of the young people in youth of Sumud, they were all from Tuwani and the villages around here.

SAMIHA: Actually, when we start, we start a few people, I was me, my older brother, there was a friends around was really fewer like when I was six seven. It's not enough for them. They can arrested us in one minute, in one Jeep even they don't be so tired. So we decide also to bigger the idea of to bigger the group to be more strong, because if we still few under this occupation we would be all arrested or will be attacked and we will be in stuck and we will never succeed to create the idea of the Youth of Sumud. So we started to public the idea around. For example, for me in my university I speak with everyone who was interesting or who's ready actually to be with this part. If he want to be an activist and he want to resist for Palestine. Also, my brother do the same. Our friend the same. We have now numbers of people like you can see we're around 20. So it's, uh, for us, it's not a very big number, enough number to protect this village and, to be enough to going around. Some people stay. Some people go to act.

SAMIHA: And one of the important things that we used to do as a Youth of Sumud that I am really proud of that. As I told you, we are a human rights defender and we are trying to to help the people that their rights is violated. The important right it's education. That is really violated in this place. For example, there is, uh, uh, schoolchildren that they came from Tuba village, that it's after these settlements that you see. It's you see this mount is full of settlements, settlers and violent settlers. After them. There is another village. So they have to pass the settlements every morning and every afternoon to come for the school and to return for their home. So they need the help to be protected because they have to come through the settlements in the middle of the settlements. They have to be protected from the settlers. And because they was attacked many time, they was hospitalized many time from the settlers, um, violent.

MAX: The the children.

SAMIHA: The children, the children of the school, they beat them, they throw them a stone, they with a stick, they follow them with a car to try, try to drive on them. They're still children. They're really small. So we decide to take this responsibility as a young people university student and all these things that we have to deal with our daily life, with our daily family and with our studying and with the with the camp. So the camps start to be our second home that we do everything we do. It's every day like you start to connect it with our life. Somehow.

MUSIC: “Ervira”

MAX: OK. So can you. Tell me what happened to your brother Sami.

SAMIHA: Yes, it's a sad story. As I told you, that we are, uh, restorating the caves for the families. So we decide to build for them a bathroom.

MAX: At Sarura? Same place?

SAMIHA: Yeah. In the same village. So it's a big, uh, like, dangerous decision to build something in C Area. Because you're not allow as a Palestinian to build any things. So we start to build this. We would have to do it because no one would come to live in anywhere in the world without bathroom. So we have to encourage them and to build bathroom to to make their life easy. So we started to build this bathroom. One day. My brother was helping us to to build this bathroom he was. I told you that Sarura is the middle of the two illegal settlements and outposts. So the settlers used to pass through this village to connect this together, to go and return.

SAMIHA: So my brother was in the middle of the road and he was helping in bringing some stone and some stuff for the to build this bathroom. So there was a two settlers in a quad. Four by four that they was driving. So they was going to kill him they keep driving on him. He was really shocked and he don't know what he have to do. He started to run and he just they keep following him because they have this, uh, quad that can drive on the stone and the bumpy road. So he just while he was running, he fell down and his right leg was still in the road. So it's just they drive on his right leg two time. They make for him to crush in his right leg. They like drive on him and they far away and they ran away. So we just.

MAX: They drove over his leg. And then they went in reverse and they drove back.

SAMIHA: Yeah. Yeah. They drive the first time and they go back and drive again. So they make for him to crush on his right legs and then they just drive and they return for the settlements. So we was really shocked from that. And we was running for him. And, uh, when we came, Sami was not awake. And when he wake, he was such shouting from pain and he was really screaming. And we don't know what you have to do because we cannot move him because it's a bones and he was he was really shouting from pain and cannot do anything. We was like we was thinking our hands was cuffed. Like, we don't we don't know what we have to do.

SAMIHA: For sure we call the ambulance just when directly when the when they like the police, the army know that they do a checkpoint. And so the, uh, the ambulance was late one hour to come and to reach the.

MAX: Wait so the ambulance before it even reached you had to go through a checkpoint.

SAMIHA: They stop in the entrance of the village of Tuwani. That's lead for the.

MAX: So they made a flying checkpoint so they couldn't get so that ambulance wouldn't get to you.

SAMIHA: Yeah, they was late. So. So he was really late to come closer. Like one hour. He was on the crowd and shouting. And so they just came and they and they took him for Hebron hospital. And, uh, he have to wait two days until he do his surgery. And he was he's still two weeks in the hospital and he was at home for two months. He cannot walking until he was like. And after two months was not really very well walking.

SAMIHA: When Sami was attacked, I was thinking that now like the other guys will be scared and they will not keep going in the idea they will stop in this point. Just was to make me really proud. That when Sami went to the hospital they back and they keep working in the in the bathroom because they say this is the reason why Sami was in the hospital and why he was attacked. So it's our responsibility to complete what he was doing. And he will he will out. He will found the bathroom, already built. And they really do. What they will say and say. We came back and he found the bathroom was already built.

MAX: And how old was he when this happened?

SAMIHA: Eh, well, last year, uh, he was like around. Now he's like twenty. And how big was twenty. The same age of me now. Yeah.

MUSIC: “Ervira”

MAX: And how about can you tell me about your younger brother.

SAMIHA: Yeah. Hamudi. Yeah. Is, uh, fifteen years old. He have had experience with occupation army because he was arrested for three time. When he was 13. He was arrested 14 the same and fifteen the same. He's trying to be an activist from his children and life like he want to be an activist because my father is an active my grandmom is an active. Everyone in my family is active. So you want to be an activist while he was 15 years old and 14 and 13.

SAMIHA: The first time he was arrested, he was arrested in the camp where we work. In the cave where we work and where we live. So he was arrested without his parents for many of hours and he was interrogated in very bad way that it's make him scared during the night, because he's a child and he cannot understand that you had a policeman interrogate him for no reason. Because he is just sitting in a camp with his family and having his dinner. It's not doesn't make sense. That's what make my father call for him, a special doctor to speak with him and to deal with him.

SAMIHA: And, uh, the second one was fourteen years old, that he was in an action to, uh, to clean the road for the cars, for the people to come reach their own village. He was helping he was arrested for the second time. It was the same. He was interrogated for many hours.

SAMIHA: And fifteen years old. A few months ago, he was arrested with my father, with my uncle in the same time because they told them that you are trying to entering in the settlements. And when they took him, They let my father and my uncle come back and they keep him. They. He slept the night in Ofer jail and he say it was the worst night of my life because they bring him in a room, with a with another two prisoner, Palestinian prisoner. He say that there was a sound of water that is going tick tick it's to make them stressed. And he said there was a light that turn off and turn on, to like, it's just to make you crazy and looking what's going on and scared you. So then. And the next day. Hamudi say they bring for us some food, there was keep the handcuffed. He was stay until the morning with handcuffs. He told them, OK, I want to eat. Can you free my hand? Can you take it over because I want to eat. And they say no for sure. No, it's not my work. You can if you manage to eat, eat. If you don't manage, it's not my business if you eat or not. So he said that I was trying to eat with my hand was cuffed.

SAMIHA: And then they say, OK, now one hour we have to go for court and he say, OK. And then he put they put him in a car that is for especially for the prisoner. And he say it was really hard because everything's iron. I cannot like. When they was driving. And they have just a small window in the top of the car. And he was Hamudi, he really is one of the people that he he cannot still without breathe for a long time. So he was shouting that he want to breathe. So they opened for him a bit of the of these windows. And then they go to close it again and he say they was drive driving really, really slow because they know that him was in really bad situation in that car. He say that this is the most thing that I hated, that the car part when they was driving me for my court. And then I found myself in Qalandiya like checkpoint. They tell him, you have you don't have any court, so go home.

SAMIHA: And after this they raid my home to arrested him. They raid my home like after 3 weeks after they arrested him. And I was asking, what are you doing here, give me the order that you can raid my home and all these things. And he was not answering me any things. He was just looking in the house. And then Hamudi came when he saw all this thing and he stop him, really badly in the wall by his neck with his hand and the give me your ID. And he starts shouting on him and they say, stay calm. And he's still a child he don't have ID because he's under 18. He don't have an ID. He said, where is your father? And my father was around in the village. So he's also start to run and they don't accept that my father can enter. They do my home a closed military zone so no one can enter. And my father say it's my home, it's my family and the they have to be sure that he's my father. I say he's my father. And then we just take him inside. When they was going out, they told him in Hebrew like I hope to don't. It will be better for you to don't see you again. And he say Hamudi say just you are coming for my home. How like. You are coming for me. I'm not coming for you. What are you doing in my home. And he said just you will be lucky if I will not meet you again.

MUSIC: “Drone Birch”

SAMIHA: So this is my brother's story. And I was feeling really sad all this time that I saw that was happening for my family, for my brothers or for my family, my mom, how she feel when her sons or daughters be in like this dangerous situation, just we believe that it's all all this for the land for Palestine and we will succeed. The idea, by the way. Because the idea is idea and it will keep life and no one can kill any idea inside you. No one can stop it. So I believe in that because we believe in that we will keep going and we will never stop. Even that there was a lot of challenge and make us weak every day. Just don't know that all the challenge that they put make us strong because we are we are trying to end the occupation and I hope that it will happen one day.

MAX: I spoke to Samiha Huraini in the village of Tuwani in December 2019, and our conversation was originally released in January 2021. Samiha’s brother Sami -- the one she talked about who had his leg run over by settlers -- that’s the same Sami whose voice you heard at the very beginning of this episode.

Sami bore witness last Saturday, May 22, when settlers from the nearby outpost Havat Ma’on set fire to the fields near Tuwani, and tried to destroy the cave in Sarura that Samiha and the Youth of Sumud have been maintaining all this time. The next morning, Sami posted this video to Facebook.

SAMI More or less one hour ago, the Israeli occupation forces raided my village of Tuwani in the South Hebron Hills. In the campaign of arrests and raids of the home of the Palestinians, searching the homes… Until this moment, three Palestinians from the village got arrested. And we thought that they are leaving but it looks the operation of arrests is still going on in the village.

MAX: Unsettled is produced by Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, Ilana Levinson, and me, Max Freedman. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music in this episode from Blue Dot Sessions.

Special thanks to Yoshi Fields, who co-produced our original episode, “The Story of Sumud,” back in 2017, and to Oriel Eisner, Emily Hilton, Isaac Kates Rose, and everyone at the Center for Jewish Nonviolence who facilitated my trip to the South Hebron Hills last year.

If you like Unsettled, please take a moment to leave us a rating and especially a review on Apple Podcasts. And don’t forget to subscribe, wherever you get your podcasts, so you never miss an episode of Unsettled.

Amjad Iraqi: Palestinians Rising

Over the last two weeks, even in the face of state and mob violence, Palestinians have been organizing mass demonstrations on both sides of the Green Line: from Jerusalem to Nazareth to Ramallah. After decades of policy designed to keep the Palestinian people fragmented, they have taken to the streets in unison to demand radical change. What does this new Palestinian uprising look like? And where will it go next?

Over the last two weeks, even in the face of state and mob violence, Palestinians have been organizing mass demonstrations on both sides of the Green Line: from Jerusalem to Nazareth to Ramallah. After decades of policy designed to keep the Palestinian people fragmented, they have taken to the streets in unison to demand radical change.

What does this new Palestinian uprising look like? And where will it go next? Producer Ilana Levinson speaks to Amjad Iraqi, a writer and editor for +972 Magazine based in Haifa.

Unsettled is produced by Ilana Levinson, Emily Bell, Asaf Calderon, and Max Freedman. Original music by Nat Rosenzweig. Additional music from Blue Dot Sessions.

Amjad Iraqi is an editor and writer at +972 Magazine. He is also a policy analyst at the think tank Al-Shabaka, and was previously an advocacy coordinator at the legal center Adalah. He is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, based in Haifa.

"Against the horror, Palestinians are still rising" (Amjad Iraqi, +972 Magazine, 5/13/21)

The Nation-State Law w/Amjad Iraqi (Unsettled, 7/24/18)

Spotify playlist: Unsettled essentials, May 2021

transcript

MAX FREEDMAN: We have seen horrific death and destruction across Israel-Palestine these last two weeks, especially in Gaza. But there has been another story happening at the same time that should not be overlooked.

Palestinians have been organizing mass demonstrations on both sides of the Green Line, from Jerusalem to Nazareth to Ramallah. After decades of policy designed to keep the Palestinian people fragmented, and in the face of daily state violence and mob violence, Palestinians have taken to the streets in unison to demand radical change.

What does this new Palestinian uprising look like? And where will it go next? My name is Max Freedman, and you’re listening to Unsettled.

Amjad Iraqi wrote about this renewed Palestinian solidarity in a recent piece called “Against the horror, Palestinians are still rising.” It was published in 972 Magazine, where Amjad is also an editor. We’ll link to that story in the show notes.

If you’ve been listening to Unsettled for a while, you might recognize Amjad’s name or his voice. We had him on the show almost three years ago to talk about the passage of Israel’s controversial “Nation State Law.”

Amjad is a Palestinian citizen of Israel, based in Haifa. He spoke to Unsettled producer Ilana Levinson last Thursday, May 20.

ILANA LEVINSON: I was hoping you could start by just describing what you're seeing throughout the West Bank and and what's on your mind in terms of these these uprisings or as you described a bit in your in your article as riots.

AMJAD IRAQI: Yeah, I mean, it's it's quite a complex picture in the end, the way that this kind of, you know, young uprising is emerging looks very different in different cities and different towns and, you know, from everywhere between sort of the Palestinian towns that are across Israel to the quote unquote, mixed cities like Haifa and Jaffa and Lydd and even to those in the occupied territories. But what these different kind of forms of these protests. What we've seen, or let's put it this way, we've seen quite a couple of common threads and common themes that go across all of them. The first is that these protests are really youth led. It's pretty extraordinary that for the most part, these young activists are really trying to almost resist or bypass the traditional leaderships, people like political parties or traditional figures or more prominent figures. They're trying to bypass them in order to assert themselves as the leaders of this movement. And it's not just about a generational thing because it's tied up with a political outlook and the political discourse, which is very present among the Palestinian youth here, which is very assertive of its Palestinian identity, of not trying to fragment itself between, you know, you know, those who are citizens of Israel or those who are under occupation. And you can feel that when you go to these protests, you can feel that vibrant youth, you can feel this desire and hunger for radical analysis of the oppression that they're facing. And the way that they're trying to mobilize these communities is really incredible.

AMJAD: This is the positive side of these protests. But, of course, these demonstrations are largely being faced by the full force of state violence. Inside Israel, for example, this is the first and foremost confrontations with the Israeli police, which are heavily militarized force. And you can see them in this full riot gear, even among even these young people, even in a city like Haifa where I'm living in, where they're even coming with horses and they're coming with stun grenades, even sort of like water cannons. You're really confronting some of the most some of the ugliest and brutal forms of state oppression. And, you know, you also have different degrees to how this is operating. But you're you know, this is like the most visual element of these demonstrations to see that kind of struggle going on in the streets and to see the youth really just go out in full force against the cops almost in a fearless way that hasn't really been seen in a long time. Young kids who've never been to a political protest in their life are showing up and are chanting these slogans, and aren't afraid to even get arrested. And these are very brutal arrests. And it's not to glorify it in any way, but that fearlessness is really showing. You can feel it on the street. You can feel it when you attend these demonstrations. You can feel it when you're talking to the people. You can tell that something's different and people are still trying to navigate it. But inside Israel, what we call like inside 48, it's been a very powerful motivator.

ILANA: Can you describe exactly what these tactics are, what the demonstrations look like? And I'm also I'm interested in your description of them in your piece, because you you. You use the word riot, and you acknowledge the complexity of that word and how politically charged it is, and I wonder why you chose to use that word.

AMJAD: Yeah, I know it's a very controversial it's a very controversial term, but I have to really give credit to some of the conversations that have been happening, especially around the Black Lives movement of last year, which really challenged us to rethink. It's not by any means the first time, of course, nor is it only in the U.S., but it really challenged us to break this sort of narrative that we've been forced into about nonviolence versus violent demonstrations. And it's not an issue about justifying violence in any way. But this dichotomy is often being determined by forces that are outside of the people who are trying to challenge oppression. And the blurred lines and the gray lines get sort of erased by this effort to say that if you want to be a legitimate protester, you cannot even so much as lift a finger on the cop who is brutally beating you and throwing you into the car. And somehow that police brutality has more legitimacy because it's part of the state. And this has been an integral part of especially international perceptions of Palestinian demonstrations, like, oh, look at them, they're throwing stones. Therefore, somehow it's justified to fire rubber bullets or live bullets or skunk water or to arrest them violently in this way. Like there's a very strange comparison that's made that inherently justifies the repression of the state. And so in trying to kind of take this word riot, which, you know, I still debate to this day, but it's it's it's try to continue that conversation that wants to break through that very false dichotomy.

AMJAD: In the end, you know, riots have always been an integral part of any movement. Even the civil rights struggle experienced these things. It wasn't just that people were purely nonviolent and peace loving and all these things that they're out there sometimes had to be some kind of defensive force. And again, it's not about justifying or not, but this is historical fact. And we saw this again with the protests last year where, you know, you had people even like burned the police station, one of the police stations down. I've forgotten which state, but it was a very symbolic image. And there were new questions being raised like, you know, what does it mean to even target an engine of state violence in that way? And it's a very complex question with no real answers but. But this is something that Palestinians are also now re-insisting here.

AMJAD: Because for the past few decades, we've almost been instructed to say, if you want to pursue your struggle, you have to pursue it nonviolently. But the barriers of the boundaries, excuse me, of nonviolence tend to be used against us and tend to almost immobilize us. And this is why these young youth are really kind of coming out. And, yes, you have some people, for example, who are confronting the police, who have some people who are maybe like burning garbage and like a garbage canister and somehow by people is a riot or violence. But and then the focus ends up moving to that rather than what the police are doing. What is the state doing? What are these lynch mobs that are roaming the streets doing? So to kind of try to reclaim that word in a way, to put it in its historical context and to say that you can't be clean cut about it. And in the end, if you're not focusing on the injustice that these people are fighting against and if you're not emphasizing that whatever violence may emanate from them, the violence that they're confronting is far more brutal than anything that they might produce. Again, not about justification or not. And yeah this is a very complex topic, but but serious questions that we need to be asking.

ILANA: Something that's interesting that I'm thinking about in in your comparison to the Black Lives Matter movement, especially over the summer, is the conversation between. People who are witnessing the uprisings over the summer and saying, well, we agree with your cause, but you're burning burning cop cars is not how you do it. And the response was, well, we've been nonviolently protesting for so long. You're just not listening. You're you're now you're paying attention because we're burning cop cars, you know? And so I'm wondering if there is a sort of similar analysis and how the uprisings that we're seeing in in Israel Palestine might reflect similarly.

AMJAD: It's very much so. And it kind of goes two ways. It's like it's only when we cause these, you know, quote unquote disturbances, it's only when we start straying from the line of what you define as nonviolence, that A, people pay attention to the people on the ground who are facing this oppression, and B, they pay attention to the most kind of explicit forms of state violence. Like, yes, you know, the protests and clashes with the police are very visual reminders that this exists. But what about the day to day forms of violence? What about the day to day forms of pressure. And it's sort of a natural kind of dilemma that a lot of activists and struggles face, like how do you keep that momentum and that attention when the violence is so, when it's the constant state of normalcy? And it's a very difficult question and we're certainly not the first ones. And this is, again, one of those things where the where the activists on the ground are saying, OK, if this is exactly how the world is going to respond, that's you know, we don't have anything to lose anymore. We're willing to push those boundaries and we're willing to break the terms which the international community has tried to assert on us. And so and so in this respect, it's it's almost like an experimentation that's going on by the protesters. To almost use this use this against against the watchers and to challenge them to say, like, I dare you to say that, you know, this, you know, quote unquote, riot is somehow more brutal than what the state is doing to us. I dare you to say that somehow the violence ends the moment we get off the streets. It's really these Palestinian youth trying to trying to put that challenge to to the observers. And again, this is really I think a lot of people really paid attention precisely to what was going on last year, because I think the conversation in the U.S., in the public discourse, in the media and the political discourse has changed drastically because people were forced to take this seriously. And it's a sad fact that, you know, it has to be taken to such extreme levels and at such high costs to the people on the streets, to the communities that are experiencing the state's violence. But if that's the way this is being taken seriously, then a lot of people are, you know, for better and worse, willing to put themselves on the line to make that happen. And time will tell if that will work in the grand scheme. But that's really where a lot of people in the Palestinian community are.

ILANA: And of course, we're seeing mob violence perpetrated against against. Palestinian citizens of Israel. Can you talk about that?

AMJAD: Yeah, this has been one of the most alarming features of this past two weeks of escalations. So in primarily in what we regard what are commonly called mixed cities, these are essentially historically Palestinian cities, which through processes of forced expulsion and ongoing gentrification and displacement, that they eventually become turn into like Jewish localities. So Jewish majority neighborhoods and so on, so forth. This is like Haifa, like Jaffa and Akka and Lydd. And what we witnessed, especially after sort of the confrontations in Gaza, in the south between Gaza and Israel, between Hamas and the Israeli forces, was that you essentially had these far right mobs roaming Arab neighborhoods and the Arab areas of these of these so-called mixed cities looking for Palestinian citizens to beat up, looking for Palestinian property like cars and homes to damage and destroy. There are people who were marking the doors of Palestine citizens even here in Haifa, you know, to give people the signal that there's an Arab family here, you can target them. These mobs were chanting racist racist slogans, including death to Arabs. And the police tend to be either joining them essentially in some of these acts of violence by invading people's homes, by firing stun grenades at Palestinian protesters and so on, or simply standing idly by and doing nothing. And this is, you know, doubly alarming for Palestinian citizens to know that not only are these mobs coming at you, but the authorities, which, you know, pose themselves as are to protect you were in fact, doing deliberately doing nothing about it and in fact, were part of the problem. And this was and this has really gripped or the fear that gripped Palestinian citizens in these places was really tremendous. People were almost terrified to come out to the streets. It really was a fear that I couldn't explain. We were having it like my family and I had it here in Haifa that at any moment that could be the potential lynch mob coming to our homes and to our into our areas.